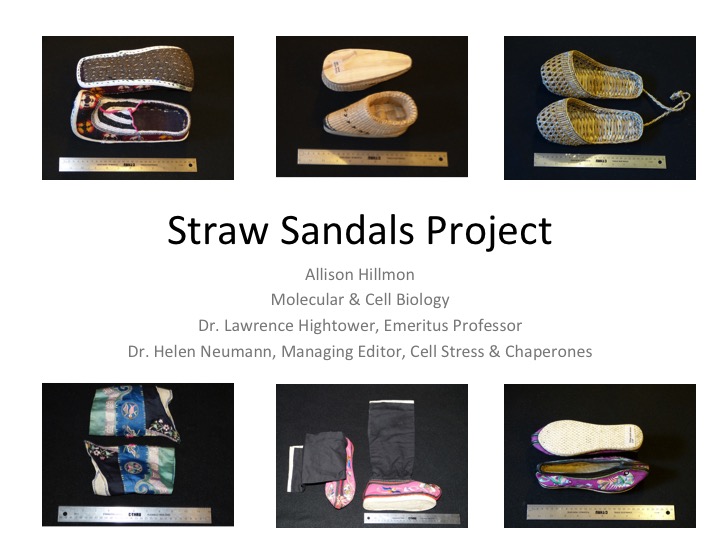

Our Straw Sandals Project student intern Allison Hillmon presented her honors thesis project at the McNair Scholars luncheon at the University of Connecticut this past semester. Allison is on the left in this photo and next to her is the Director of the McNair Scholars Program Dr. Renée Gilberti. The gallery below is Allison’s PowerPoint presentation just to inform her fellow McNair Scholars and their mentors on what she was doing. I think it is the first public talk about the Straw Sandals Project. Allison successfully completed her honors thesis and I will post some of her writings here in the near future. In addition to re-photographing the entire SSP collection in a much more professional manner, Allison wrote a scholarly report updating the story of Kennewick Man, an ancient skeleton that washed out of a bank along the Columbia River in Washington state, and she wrote an imaginative essay on what it may have been like to be living there in those pre-historic times almost 10,000 years ago!

Our Straw Sandals Project student intern Allison Hillmon presented her honors thesis project at the McNair Scholars luncheon at the University of Connecticut this past semester. Allison is on the left in this photo and next to her is the Director of the McNair Scholars Program Dr. Renée Gilberti. The gallery below is Allison’s PowerPoint presentation just to inform her fellow McNair Scholars and their mentors on what she was doing. I think it is the first public talk about the Straw Sandals Project. Allison successfully completed her honors thesis and I will post some of her writings here in the near future. In addition to re-photographing the entire SSP collection in a much more professional manner, Allison wrote a scholarly report updating the story of Kennewick Man, an ancient skeleton that washed out of a bank along the Columbia River in Washington state, and she wrote an imaginative essay on what it may have been like to be living there in those pre-historic times almost 10,000 years ago!

Molecular Weaving for Weavers!

I am sure that there are small numbers of chemists and materials scientists who weave for a hobby and for relaxation, but when I read the article in Science (22 January 2016) discussed here, I suspected that I would be rare if not unique in being equipped to explain this remarkable chemical synthesis to my weaver friends!

I hope that I can do justice to both communities. I tend to view the Straw Sandal Project website as a place on the web for biologists who never quite got over wanting to be anthropologists and for weavers and shoe designers looking for inspiration. But it turns out this biologist majored in chemistry at a small college in Virginia, Hampden-Sydney College with only 500 students at the time and a chemistry department that was small in size but large in opportunities to learn and grow as a scientist. So, even though I have not read a hard core chemistry research report in years, thanks to some great teachers years ago, I had no problem with the organic and inorganic chemistry in the report by Y. Liu et al. on page 365 titled “Weaving of organic threads into a crystalline covalent organic framework”.

In some ways, it was more challenging to open the pages of Irene Emery’s classic The Primary structure of Fabrics and begin searching for similar weaves and nomenclature. How many chemists I wonder have a copy of Irene Emery’s opus within arm’s reach! Science devoted a very nice cover to the story. The cover was described as an “Illustration of woven molecular fabric.”

My thought was, OK how will my weaver friends see this? I think Irene would agree that this construction is a balanced plain weave with the warps and wefts made of the same material. So far so good. But what about the thread (some would say yarn, but I think the chemists are good with using the term thread). I would call it plied thread composed of Z-twisted elements. Oops, this is not what the chemists made. They used a copper I cation to bind two identical organic molecules. Four nitrogen atoms, two from each organic molecule formed a reversible coordination complex with the cation. The organic molecules, think of each as a short piece of thread, are held in just the right position so that they cross or interlace.

My thought was, OK how will my weaver friends see this? I think Irene would agree that this construction is a balanced plain weave with the warps and wefts made of the same material. So far so good. But what about the thread (some would say yarn, but I think the chemists are good with using the term thread). I would call it plied thread composed of Z-twisted elements. Oops, this is not what the chemists made. They used a copper I cation to bind two identical organic molecules. Four nitrogen atoms, two from each organic molecule formed a reversible coordination complex with the cation. The organic molecules, think of each as a short piece of thread, are held in just the right position so that they cross or interlace.

My weaver friends are going to want to know if a loom was used. I think that this copper 1 coordination complex is a molecular loom. Think of the two organic molecules as threads attached to a loom like warps strung on a typical weaving loom in preparation for weaving. To extend the threads, the chemist adds a small linear reactive molecule, an imine in this case. The imines attach to the four ends of the two threads on the molecular loom if you will. Now the other reactive ends of the imines are still available to add another molecular thread to each one, so the weaving starts by extending the length of the original threads. Or alternatively, another molecular loom can be added to each free end of the imine group. At the end of the molecular weaving, the copper cation can be released and so the molecular loom is essentially released from the tiny piece of woven molecular material. If you look at the cover image, you can see where each tiny loom was situated. Wherever the two threads interlace is where the copper 1 coordination complex, the molecular loom, was set up. So there are many tiny looms at work at the same time to weave a molecular textile. Each crossover point marks the place where a molecular loom set up a starting place with two molecular threads oriented for weaving in four different directions.

How will this new kind of woven material be used? Certainly a major use will be in nano-scale (a nanometer is one billionth of a meter, if you can visualize that: I cannot!) machines to create special environments for chemical reactions or to create surfaces on which to organize mechanical tasks. Another idea presented in a perspectives article titled “Interlacing molecular threads” by Enrique Gutierrez-Puebla in the same issue of Science is that these materials may be considered as molecular sponges capable of sopping up metal ions in liquid waste. An idea that popped into my mind as I was reading an article on new ways to restore and protect works of art, especially out of doors, such as murals and mosaics, may be to cover them with just the right kind of molecular woven material tailored to counteract corrosive chemicals specific to the environment of each piece. See article on recent restoration techniques.

One final observation is that most of the authors of the scientific paper are Asian scientists. I wonder if in China and Japan they wore and played with woven baskets and scandals. Did early contact with woven materials influence their creative thinking about approaches to molecular weaving?

Progress on the Collection thanks to Allison Hillmon

I have a new assistant working behind the scenes of the Straw Sandals Project. Allison Hillmon is a McNair scholar, students with the goal of obtaining Ph.D. degrees in STEM programs where they are in under-represented groups. She is a senior at the University of Connecticut who became interested in the project and has decided to do her senior thesis on an aspect of it. She has been re-photographing the entire collection in a more professional manner that will make the sandals more useful.

See the new image below of a pair of French straw sandals on a black felt background. Soon, the entire collection will be displayed on our website in this way thanks to Allison’s efforts.

Moroccan Shoes in Paris

My friend and colleague Robert M. Tanguay and his wife Nicole were on an extended visit to Paris recently and they found a small shop that had the Moroccan hand woven raffia shoes pictured here for sale. Robert and Nicole purchased three pairs and generously donated them to the Straw Sandals Project. There are no signs of wear on the bottoms of the soles and yet the shoes, especially the vamps, do not appear to be made recently. None of them is stamped “made in……” although there is a stamp mark on the inner sole of one pair that I may ultimately be able to trace. I think it is safe to assume that they were made in Morocco, based on the distinctive styling of these shoes. Why is this even a question you may ask? The distinctive weave seen here, and I have read that it arose in North Africa in what is the region of present day Morocco, is very popular today among high end shoe designers.

The second image shows a pair of the Moroccan shoes from Paris along with a pair of Ferragamo flats on your left and a pair of Carrie Forbes flats on your right. A close-up in the third image shows the identical Moroccan weave in each shoe. The latter two pairs of shoes were made in Italy.

The next image shows a pair of Joseph Azagury woman’s shoes designed in London and made in Italy. Joseph Azagury shoes are now handcrafted in London. Again, the distinctive Moroccan weave was used to make the vamp. The designer Joseph Azagury was born in Morocco, raised in Italy and now lives in London! The final image shows the Azagury shoe beside a Moroccan shoe, verified as made in Morocco, that is item Mor2 in the Straw Sandals Project collection. The close-up shows the Moroccan weave in each shoe. Contemporary designers are helping the weavers and their ancient handcrafting and distinctive weaving to survive in our modern world.

Forest Shoes

Friend of the Straw Sandals Project Donna Crispin just completed a beautiful pair of hand woven shoes. Donna told me that she crafted them from plaited willow bark from her yard. To this material she added hand spun paper cord, commercial paper cord, yellow cedar and red cedar bark. Here is a peek at the shoes:

Donna very aptly named them Forest Shoes. She has just opened a blog on which she describes how the materials were harvested and prepared as well as how the shoes were constructed. This is a great opportunity to interact with the weaver and trade information and questions. Donna and I invite you to join the blog here.

Kaycee in Prada and Joseph Azagury

Friend of the Straw Sandals Project and shoe model Kaycee donates her time and experience with contemporary footwear. We learn a lot more at photo sessions during which Kaycee wears and walks in a pair of shoes, describing how they feel and work. Here she is wearing a pair of Prada woven straw kitten heels with the front of the vamp made of alligator skin dyed a slate color and patent leather trim dyed salmon. The rest of the vamp is composed of a piece of plain weave that looks to contain three different kinds of fibers. The soles appear to be a combination of leather, synthetic materials and possibly wooden stacked heels. They are stamped Prada, made in Italy, vero cuolo, size 37. Kaycee commented that these shoes are surprisingly comfortable. The designer used the readily stretchable straw material in just the right place in the vamp to allow the foot to expand at its widest point across the ball of the foot when weight is applied during walking or standing. These shoes are good examples of the broad use of a variety of different materials in contemporary shoe construction. It is interesting that woven straw, traditionally the material of rural peoples, is among the materials used by high fashion shoe designers for urban lifestyles. The shoes are identified as It2 in the collection. (purchased on Ebay, rerunsboutiqueshop, Knoxville, TN, USA)

The second pair of shoes has an interesting story. It was marked It1 in the collection. The soles of theses shoes are stamped with Joseph Azagury, London, made in Italy, size 37.5. The vamps are straw and the construction method is twining using thick warps and thin wefts. The vamps entirely made from woven straw have that great quality of conforming easily to the shape and expansion of Kaycee’s feet.

It immediately caught my eye that the vamp was sewn into the leather footbed using a method characteristic of Moroccan shoes. We included the It1 Azagury shoes in one of our computer runs comparing footwear characteristics by cluster analysis. These shoes clustered with Moroccan shoes in the collection. It was one of the best indications early on that the similarity programs, the same ones used by biologists to determine phylogenetic relationships among plants and animals, were generating useful information about sandal relationships. The Joseph Azagury It1 shoes are shown below with Mor2, authentic Morroccan shoes.

Now, I had to learn more about the designer, Joseph Azagury. His biography on-line revealed that he learned the footwear trade as a shoe salesman at Harrods of London, studied at London’s Cordwainers College, and that the JA collection is considered a leading designer label in the United Kingdom. He has worked in Italy, also Spain and the USA, and likely had come to appreciate the high quality of materials and workmanship of high end shoes made in Italy. So, what about the validity of our computer program that clustered with Morocco these shoes designed in London and made in Italy? It turns out that Joseph Azagury was born and raised in Morocco! He came to London as a young man. For the shoes shown below, he was obviously strongly influenced by the design and construction of shoes from his native land. The seller told me that the shoes had been purchased at an estate sale in Scottsdale, AZ, USA (Purchased on Ebay in the on-line store daytona7beach)

Woven Goods in Bhaktapur, Nepal

My friend Donna Crispin, a fiber artist from Eugene Oregon, took these photos during a recent family trip to Nepal. Bhaktapur is near the capitol and is a popular city among tourists. It was great to see these straw sandals among the ‘products’ for sale in the shop. They are a simpler version of item #NP1 in The Collection, made with essentially the same construction techniques, but no decoration. NP1 has an interesting history. It was purchased at a market in New York City and the buyer thought it was from Nepal. This pretty much confirms it!

Migrating woven shoes from Eastern Europe?

This is the story of two almost identical pairs of woven shoes. The first pair was purchased on Ebay in December of 2012. The owner of Prioritybargains told me that they were found in a flea market in Northwest Oklahoma. He said that there were no marks on the shoes and so he assumed they may have been produced locally, perhaps by a Native American weaver. I decided to add them to the Americas category of the Straw Sandals Project Collection as Am3 and when they were described for the Straw Sandals Catalog, they were assigned the tag NAm9. The important fact to keep in mind is that the provenance of these shoes is unknown. Then in May of 2013, the second pair was purchased from Etsy store Terrossi located in the United Kingdom. The seller told me that these shoes were hand made in Bulgaria (Eastern Europe) at a Fairtrade cooperative. They were entered into the Collection as Bu1 and they were assigned a tag of EEu3 by the software used in the Straw Sandals Catalog.

How were these shoes described in the Catalog and how did the relationship programs handle them? The shoes are shown in the image below:

If the same construction methods were used and the same or very similar natural fibers were used to make them, we would expect that they would be treated much the same in the Catalog. There are two major parts to the process. The first part is the description of the shoes, done by humans, and the second part is the construction of phylogenetic trees and cluster diagrams, done by computer software. Decisions are made in the first part that are likely to have subjective components. My colleague Helen and I sit together and discuss each shoe as we respond to the descriptors on the Catalog Entry page. We come to agreement on each response. Our responses are entered into the Catalog’s electronic database and the description in the form of a string of numbers is generated. These number strings can be processed by the phylogenetic relationship software. This probably has never been done before for woven footwear. In past history, a sandal description has been a paragraph or two of text. For Nam9 (collection item Am3) the description is shown here, each number in the string corresponding to a specific response to each of 38 descriptors:

4111111-91465-91111222233-965-911113233-931. Here is pair #2, EEu3 (Bu1):

4111111-91165-91111222233-965-911113233-932

(Note that the first descriptor on the Catalog Entry page is not scored so the descriptor string above includes descriptors 2-39)

There are only two descriptors that were scored differently, #11 and #39:

#11. Decoration

#39. Overall Sole Shape

For item 11, decoration, we scored the Am3 pair as “Pattern created by main construction technique”, and we scored the Bu1 pair as “None”. For item 39, overall sole shape, we scored the Am3 pair as “Symmetrical”, and we scored the Bu1 pair as “Asymmetrical”. The decorative difference across the toe box is clear but the sole shape is a more subjective call since wearing the shoes and/or packing them can alter their shapes. Also the Am3 pair is larger and perhaps more deformable. However, on second look, we would not change our responses.

What can we conclude about the origin of the pair purchased in NW Oklahoma? It is certain that these shoes were made by a weaver using the same construction methods as the Bulgarian shoes, and more than that, the same or very similar natural fiber materials were used. These included three different materials or at least different parts of the same or very similar plant for the warp, weft and selvage. Microscopic examination of cross sections of the natural fibers could identify the plants used and we could then determine where these plants live. Currently we are relying on visual inspection. Thus, it is likely that both pairs of shoes were made in the same geographic region or by weavers originally from the same region. Based on the information at hand, it seems most likely to me that both pairs, Bu1 and Am3, were made in or near Bulgaria. I have given Am3 a second tag, Bu2, in the Collection.

We will probably never know how the Am3 shoes ended up in a flea market in NW Oklahoma. I favor the idea that they were made in Eastern Europe and sent by a relative or friend to someone living in Oklahoma or picked up by a tourist or military person in Bulgaria and brought home. Perhaps they were purchased in a store in yet another country. There are other possibilities of course, such as shoes in the style of Am3 being made by Native American weavers in Oklahoma, one of whom may have found his or her way to Eastern Europe with the weaving style eventually reaching a fair trade cooperative in Bulgaria where Bu1 was made. Perhaps the relationship software will help us decide the most likely geographic origin and direction of migration!

I will answer the question “How do a couple of differences in how the descriptors are scored affect sandal relationships?” in a future news post.

Shoes Woven by Donna Sakamoto Crispin

It is a pleasure to introduce a pair of woven shoes crafted by Donna Sakamoto Crispin, a fiber artist in Eugene, Oregon. Donna is a friend of the Straw Sandals Project with whom I connected through Facebook. She has made some remarkable pieces using woven materials, handmade paper and combinations of natural materials. Friend Donna on her Facebook page to see some of her creations. A third generation Japanese-American, Donna incorporates Japanese craft traditions into many of her fiber art works. This inspiration can be seen in the woven shoes she recently completed, shown here:

Several archaeologists have expressed the idea that of all human artifacts, the rich detail preserved in woven baskets and shoes provides us the most detailed view of the mental decisions and memory of the weaver. I first read this notion in James M. Adovasio’s book Basketry Technology: A Guide to Identification and Analysis along with my favorite descriptor of woven foot wear, straw sandals are baskets for the feet. As I plan to describe in a future post, how and why Donna chose the materials used to make these shoes and the decisions she made in their construction, gives us a contemporary example of how the mind of the weaver is reflected in the shoes she wove. We may have a better understanding for example of the mind of the ancient weaver who crafted about ten thousand years ago the Fort Rock sandals found in a cave in central Oregon by Luther S. Cressman, father of Oregon anthropology. Remarkably, these sandals are now in the University Oregon Natural History Museum in Eugene, the same city in which Donna wove these lovely shoes.

Reed Boots with Elevated Soles from South China

My fellow curator Ruixing Lu contributed these boots along with a description in Chinese of their purchase in a rural area near the city of Wenzhou in Zhejiang Province, along the coast south of Shanghai. Ruixing’s daughter Lu Qi (luki) is in process of tanslating the document but there was a bit of English, Phragmites australis (Cav,) Trin. exSteud, just enough to tell us that the main construction material is the common reed. This is large perennial grass with a distinctive fuzzy seed head in fall and winter that grows in wetlands globally in temperate and tropical regions. These boots look just perfect for the wet coastal plain on the edge of Wenzhou that is intensively farmed. The wooden soles are essentially raised platforms good for walking in shallow water and mud, similar to some Japanese shoes. The uppers consist of a netting, likely made from dried leaves from the reeds on which material consisting mainly of the seed heads is woven. This creates a felt-like vamp that is very light weight and airy. This would allow wet feet to dry quickly inside of the boots. In a subtropical region like this one, waterproof footwear would cause feet to sweat and no doubt this would promote the growth of fungus and bacteria. Fast-drying footwear keeps the feet much healthier in tropical climates.