Kennewick Man: A Coevolution of Society and the Genome

The divide between the experimental truths of the hard sciences and the nuances of human culture grows increasingly narrow as each provides important feedback for the other. Rather than existing in separate realms, biological research endeavors often provide eye-opening explanations and rebuttals to age-old traditions and belief systems, and vice versa. Each viewpoint’s response to the other illustrates a dialogue that has only intensified over the centuries: Is scientific evidence more reputable than abstract human intuitions and social cues? Or do historical kinships and ancestral knowledge trump modern research methods? This important relationship became embodied by the discovery and exploration of Kennewick Man, an ancient Native American whose skeletal remains raised both inquiry and controversy among biologists and anthropologists and the resident Native American and Plateau tribes of the West and Northwestern United States. While his life concluded eight to nine thousand years ago, investigators have begun to imagine the human male living among his people on or near the Columbia River in Washington, and how he arrived at the river as his final resting place.

The discovery of Kennewick Man by Dr. James Chatters and colleagues in 1996 was magnified as a hallmark achievement when the findings of similar artifacts at the time were considered; only three other unveilings of human remains had surfaced prior to his uncovering along the Columbia River, marking him as only the second complete skeleton located on the North American continent (Chatters 2016, 55). Not only did his good preservation promise more than enough organic material for genetic, time period, and other analyses, researchers could begin to predict how he fit or clashed with the lineages of the American Indians of colonial America, or perhaps the pre-colonial tribes who preceded these natives. However initial radiocarbon dating soon estimated a birth of eight thousand four hundred years ago. The skull was also notable for its dissimilarities to more modern Native American peoples, displaying a “narrow face [and skull] and receding cheekbones, unlike the short, round skulls . . . [and] broad, flat faces” of the recent American Indians local to the skeleton’s discovery site (Chatters 2016, 63). This test in combination with craniofacial analyses refuted some speculations that Kennewick Man was a more current discovery.

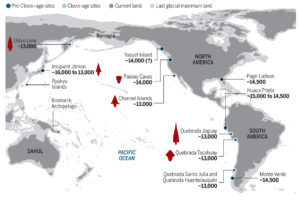

Other opinions that the skeleton represented that of an ancient European were also undermined in light of historical migratory patterns. Certain characteristics of Kennewick Man’s long bones tempted the potential connection to modern Europeans, but as many pre-colonial tribes once migrated from East Asia and Europe to North America, many skeletal traits have been preserved over time across even these global populations (Chatters 2016, 64). This original migratory wave thus gave rise to all modern Native Americans. Divisions subsequently occurred around thirteen thousand years ago consisting of the Athabascans and northern Amerindians and the southern North American Amerindians, and gene flow also spread between the northern populations and the more northern Inuit people who arose from a completely separate migration originating from Siberians in northern Asia from around twenty-four thousand years ago (Raghavan et al. 2015). Even considering genetic mixing, Kennewick Man succeeded these early arrivals after only about three to four thousand years, making him an almost absolute ancestor to all Native Americans who followed him. More recently published analyses of skeletal material support this, reflecting high genetic affinities to Northern Native Americans according to model-based clustering of existing autosomal data (Rasmussen 2015).

Although Kennewick Man’s deep historical roots helped elucidate pre-historic migration into what is now known to be the United States, his distinct features and skeletal make-up appeared to cause more unrest between interested parties than it did placate pressing questions. Ownership of the skeleton was hotly debated between northwestern North American tribes, and also between themselves and the scientists who sought to claim the ground-breaking remains for the sake of research. Simple negotiation was ruled out as the issue soon became a concern for the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), legally complicating the argument as to whom Kennewick Man rightfully belonged to (Rasmussen 2015). While the act highlights and enforces important distinctions and protections between the rights of individual families over their dead kin as well as the interests in sacred artifacts for the future generations of an entire tribe, ample argument has been made against NAGPRA as vengeful rather than advocative legislation. Some have held that the act wrongly exceeds its responsibility to solely guard the cultural rights of modern-day Native Americans and instead gives tribes the ability to gain a powerful foothold of revenge against the original white Americans, enabling them to steal back what was once unjustly seized from the Native American tribes who preceded the European settlers (Conklin 2014). However an equally fervent claim exists that the assertiveness of NAGPRA is all but necessary. The rights and interests of Native Americans past and present are being recognized increasingly as valid pursuits on the same level of priority as the more predominant “white” scientific groups, and the handling and collection of their human and cultural artifacts should be monitored to prevent encroachment and desecration. On top of these concerns is also an age-old wariness that, especially in the case of Kennewick Man, the identification of Native American remains as potentially non-Native American (and therefore excluding the relevance of NAGRPA) is in fact a propaganda device, bending scientific results in favor of “white” possession of Native American belongings (Conklin 2014). NAGPRA thus presented ambiguity that challenged researchers with the dilemma of advocating for either their promising findings on human ancestry or the voices of exploited yet historically prominent peoples.

In 2004 the legal conflict sided with scientific endeavors, allowing further study of Kennewick Man after the U.S. Corps of Engineers received significant pressure from citizens, scientists, and statesmen alike in favor of analyzing the skeleton (Rasmussen 2015). The Umatilla fought for ownership most notably for the remains due to religious discouragement against scientific exploitation of the dead, particularly skeletons. Repatriation was advocated as a viable course of action by the Corps, but DNA results would place him differently. Despite strong sentiment that Kennewick Man had been a direct ancestor of modern Native Americans, analyses of his skull determined him as a much closer ancestor of the Polynesian and Ainu peoples. Even given his predominantly Pacific and ancient East Asian origins, genomic data also pinpointed his strongest affinities to be with the Colville people, whom research supported most securely as potential rightful owners of the human remains, a conclusion supported by both autosomal and mitochondrial DNA as well as Y chromosome data (Rasmussen 2015, Raghavan 2015).

The discovery and subsequent debate over Kennewick Man exemplifies not the black-and-white authority of anthropological and biological science, but rather the complementary relationship between social constructs and research. While the true genetic identity of Kennewick Man was revealed to be far from an original Native American, the cultural intuitions of local tribes rightfully challenged and ultimately supported recent scientific revelations about the historical timeline of the skeleton and others like it that may have once existed. NAGPRA served its goal, implementing much-warranted checks and balances to scientists’ domain of curiosity. Kennewick Man stands not only as a symbol of Native American legacy and authority as people and cultures to be protected and celebrated, but also a milestone that helped restore good faith about United States governmental research to modern tribal peoples.

Work Cited

Chatters, James C. “Kennewick Man.” Northern Clans, Northern Traces: Journeys in the Ancient Circumpolar World. Smithsonian Institution, 2004. Web. 27 April 2016.

Chatters, James C. Ancient Encounters: Kennewick Man and the First Americans. New York: Touchstone, 2001. Print.

Conklin, Kenneth R. “The NAGPRA Law, and the Kennewick Man Controversy. Includes an article in September 2014 Smithsonian Magazine summarizing the Kennewick case and what was discovered.” 2014. Web. 27 April 2016.

Raghavan, Maanasa et al. “Genomic Evidence for the Pleistocene and Recent Population History of Native Americans.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 349.6250 (2015): aab3884. PMC. Web. 27 Apr. 2016.

Rasmussen, M., et al. “The Ancestry and Affiliations of Kennewick Man.” Nature 523.7561 (2015): 455-8. Web.